Experts on conflict predict unrest, but America has a long way to go before it is as divided as it was in 1861

The Sunday Times

January 9, 2022

Violence is in the air. No one who saw the shocking scenes during the Capitol riot in Washington on January 6, 2021, can pretend that it was just a big misunderstanding. Donald Trump and his allies attempted to retain power at all costs. Terrible things happened that day. A year later the wounds are still raw and the country is still polarised. Only Democratic leaders participated in last week’s anniversary commemoration; Republicans stayed away. The one-year mark has produced a blizzard of warnings that the US is spiralling into a second civil war.

Only an idiot would ignore the obvious signs of a country turning against itself. Happy, contented electorates don’t storm their parliament (although terrified and oppressed peoples don’t either). America has reached the point where the mid-term elections are no longer a yawn but a test case for future civil unrest.

Predictably, the left and right are equally loud in their denunciations of each other. “Liberals” look at “conservatives” and see the alt-right: white supremacists and religious fanatics working together to suppress voting rights, women’s rights and democratic rights. Conservatives stare back and see antifa: essentially, progressive totalitarians making common cause with socialists and anarchists to undermine the pillars of American freedom and democracy. Put the two sides together and you have an electorate that has become angry, suspicious and volatile.

The looming threat of a civil war is almost the only thing that unites pundits and politicians across the political spectrum. Two new books, one by the Canadian journalist Stephen Marche and the other by the conflict analyst Barbara Walter, argue that the conditions for civil war are already in place. Walter believes that America is embracing “anocracy” (outwardly democratic, inwardly autocratic), joining a dismal list of countries that includes Turkey, Hungary and Poland. The two authors’ arguments have been boosted by the warnings of respected historians, including Timothy Snyder, who wrote in The New York Times that the US is teetering over the “abyss” of civil war.

If you accept the premise that America is facing, at the very least, a severe test of its democracy, then it is all the more important to subject the claims of incipient civil war to rigorous analysis. The fears aren’t baseless; the problem is that predictions are slippery things. How to prove a negative against something that hasn’t happened yet? There’s also the danger of the self-fulfilling prophecy: wishing and predicting don’t make things so, although they certainly help to fix the idea in people’s minds. The more Americans say that the past is repeating itself and the country has reached the point of no return, the more likely it will be believed.

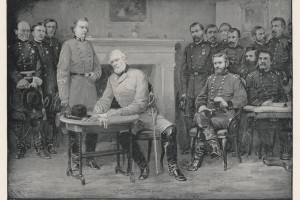

Predictions based on comparisons to Weimar Germany, Nazi Germany, the Russian Revolution and the fall of Rome are simplistic and easy to dismiss. But, just as there is absolutely no basis for the jailed Capitol rioters to compare themselves to “Jews in Germany”, as one woman recently did, arguments that equate today’s fractured politics with the extreme violence that plagued the country just before the Civil War are equally overblown — not to mention trivialising of its 1.5 million casualties.

There simply isn’t a correlation between the factors dividing America then and now. In the run-up to the war in 1861, the North and South were already distinct entities in terms of ethnicity, customs and law. Crucially, the North’s economy was based on free labour and was prone to slumps and financial panics, whereas the South’s depended on slavery and was richer and more stable. The 13 Southern states seceded because they had local government, the military and judicial institutions on side.

Today there is a far greater plurality of voters spread out geographically. President Biden won Virginia and Georgia and almost picked up Texas in 2020; in 1860 there were ten Southern states where Abraham Lincoln didn’t even appear on the ballot.

When it comes to assessing the validity of generally accepted conditions for civil breakdown, the picture becomes more complicated. A 2006 study by the political scientists Havard Hegre and Nicholas Sambanis found that at least 88 circumstances are used to explain civil war. The generally accepted ones include: a fragile economy, deep ethnic and religious divides, weak government, long-standing grievances and factionalised elites. But models and circumstances are like railway tracks: they take us down one path and blind us to the others.

In 2015 the European think tank VoxEU conducted a historical analysis of over 100 financial crises between 1870 and 2014. Researchers found a pattern of street violence, greater distrust of government, increased polarisation and a rise in popular and right-wing parties in the five years after a crisis. This would perfectly describe the situation in the US except for one thing: the polarisation and populism have coincided with falling unemployment and economic growth. The Capitol riot took place despite, not because of, the strength of the financial system.

A country can meet a whole checklist of conditions and not erupt into outright civil war (for example, Northern Ireland in the 1970s) or meet only a few of the conditions and become a total disaster. It’s not only possible for the US, a rich, developed nation, to share certain similarities with an impoverished, conflict-ridden country and yet not become one; it’s also quite likely, given that for much of its history it has held together while being a violent, populist-driven society seething with racial and religious antagonisms behind a veneer of civil discourse. This is not an argument for complacency; it is simply a reminder that theory is not destiny.

A more worrying aspect of the torrent of civil war predictions by experts and ordinary Americans alike is the readiness to demonise and assume the absolute worst of the other side. It’s a problem when millions of voters believe that the American polity is irredeemably tainted, whether by corruption, communism, elitism, racism or what have you. The social cost of this divide is enormous. According to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project: “In this hyper-polarised environment, state forces are taking a more heavy-handed approach to dissent, non-state actors are becoming more active and assertive and counter-demonstrators are looking to resolve their political disputes in the street.”

Dissecting the roots of America’s lurch towards rebarbative populism requires a particular kind of micro human analysis involving real-life interviews with perpetrators and protesters as well as trawls through huge sets of data. The results have shown that, more often than not, the attribution of white supremacist motives to the Capitol rioters, or anti-Americanism to Black Lives Matter protesters, says more about the politics of the accuser than the accused.

Social media is an amplifier for hire — polarisation lies at the heart of its business models and algorithms. Researchers looking at the “how” rather than just the “why” of America’s political Balkanisation have also found evidence of large-scale foreign manipulation of social media. A recent investigation by ProPublica and The Washington Post revealed that after November 3, 2020, there were more than 10,000 posts a day on Facebook attacking the legitimacy of the election.

In 2018 a Rasmussen poll asked American voters whether the US would experience a second civil war within the next five years. Almost a third said it would. In a similar poll conducted last year the proportion had risen to 46 per cent. Is it concerning? Yes. Does it make the prediction true? Well, polls also showed a win for Hillary Clinton and a landslide for Joe Biden. So, no.