Long associated with Aphrodite, oysters graced the menus of Roman orgies, Gold Rush eateries and Manhattan brothels.

February 4, 2021

The oyster is one of nature’s great survivors—or it was. Today it is menaced by the European green crab, which has been taking over Washington’s Lummi Sea Pond and outer coastal areas. Last month’s emergency order by Gov. Jay Inslee, backed up by almost $9 million in funds, speaks to the threat facing the Pacific Northwest shellfish industry if the invaders take over.

As any oyster lover knows, the true oyster, or oyster ostreidae, is the edible kind—not to be confused with the pearl-making oysters of the pteriidae family. But both are bivalves, meaning they have hinged shells, and they have been around for at least 200 million years.

King James I of England is alleged to have remarked, “He was a very valiant man, who first adventured on eating of oysters.” That man may also have lived as many as 164,000 years ago, when evidence from Africa suggests that humans were already eating shellfish.

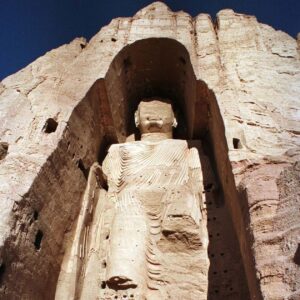

The ancient Greeks were the first to make an explicit connection between oysters and, ahem, sex. Aphrodite, the goddess of love, was said by the 8th-century B.C. poet Hesiod to have risen from the sea foam when the Titan god Kronos cut off the genitals of his father Ouranos and hurled them into the sea. Thereafter, Greek artists frequently depicted her emerging from a flat shell, making a visual pun on the notion that oysters resemble female genitalia.

By Roman times it had become a truism that oysters were an aphrodisiac, and they graced the menus of orgies. The Roman engineer Sergius Orata, who is credited with being the father of underfloor heating, also designed the first oyster farms.

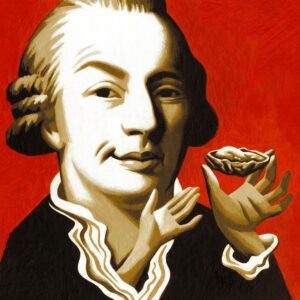

ILLUSTRATION: THOMAS FUCHS

Many skills and practices were lost during the Dark Ages, but not the eating of oysters. In his medical treatise, “A Golden Practice of Physick,” the 16th-century Swiss physician Felix Platter recommended eating oysters for restoring a lost libido. The great Italian seducer Giacomo Casanova clearly didn’t suffer from that problem, but he did make oysters a part of his seductive arsenal: “Voluptuous reader, try it,” he urged in his memoirs.

In the 19th century, oysters were so large and plentiful in New York and San Francisco that they were a staple food. A dish from the Gold Rush, called the Hangtown Fry, was an omelet made with deep fried oysters and bacon and is often cited as the start of Californian cuisine. In New York there were oyster restaurants for every class of clientele, from oyster cellars-cum-brothels to luxury oyster houses that catered to the aristocracy. The most sought-after was Thomas Downing’s Oyster House on 5 Broad Street. In addition to making Downing, the son of freed slaves, an extremely wealthy man, his oyster restaurant provided refuge for escaped slaves on the Underground Railroad to Canada.

At least since the 20th century, it has been well known that oysters play a vital role in filtering pollution out of our waters. And it turns out that their association with Aphrodite contains an element of truth as well. A 2009 study published in the Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences found a link between zinc deficiency and sexual dysfunction in rats. Per serving, the oyster contains more zinc than any other food. Nature has provided a cure, if the green crab doesn’t eat it first.