Napoleon’s bicorne and Santa Claus’s red cap both trace their origins to the felted headgear worn in Asia Minor thousands of years ago.

December makes me think of hats—well, one hat in particular. Not Napoleon’s bicorne hat, an original of which (just in time for Ridley Scott’s movie) sold for $2.1 million at an auction last month in France, but Santa’s hat.

The two aren’t as different as you might imagine. They share the same origins and, improbably, tell a similar story. Both owe their existence to the invention of felt, a densely matted textile. The technique of felting was developed several thousand years ago by the nomads of Central Asia. Since felt stays waterproof and keeps its shape, it could be used to make tents, padding and clothes.

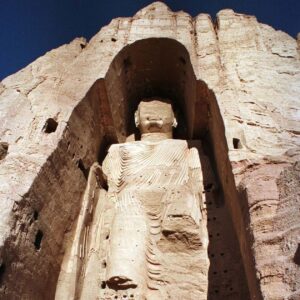

The ancient Phrygians of Asia Minor were famous for their conical felt hats, which resemble the Santa cap but with the peak curving upward and forwards. Greek artists used them to indicate a barbarian. The Romans adopted a red, flat-headed version, the pileus, which they bestowed on freed slaves.

Although the Phrygian style never went out of fashion, felt was largely unknown in Western Europe until the Crusades. Its introduction released a torrent of creativity, but nothing matched the sensation created by the hat worn by King Charles VII of France in 1449. At a celebration to mark the French victory over the English in Normandy, he appeared in a fabulously expensive, wide-brimmed, felted beaver-fur hat imported from the Low Countries. Beaver hats were not unknown; the show-off merchant in Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales” flaunts a “Flandrish beaver hat.” But after Charles, everyone wanted one.

Hat brims got wider with each decade, but even beaver fur is subject to gravity. By the 17th century, wearers of the “cavalier hat” had to cock or fold up one or both sides for stability. Thus emerged the gentleman’s three-sided cocked hat, or tricorne, as it later became known—the ultimate divider between the haves and the have-nots.

The Phrygian hat resurfaced in the 18th century as the red “Liberty Cap.” Its historical connections made it the headgear of choice for rebels and revolutionaries. During the Reign of Terror, any Frenchman who valued his head wore a Liberty Cap. But afterward, it became synonymous with extreme radicalism and disappeared. In the meantime, the hated tricorne had been replaced by the less inflammatory top hat. It was only naval and military men, like Napoleon, who could get away with the bicorne.

The wide-brimmed felted beaver hat was resurrected in the 1860s by John B. Stetson, then a gold prospector in Colorado. Using the felting techniques taught to him by his hatter father, Stetson made himself an all-weather head protector, turning the former advertisement for privilege into the iconic hat of the American cowboy.

Thomas Nast, the Civil War caricaturist and father of Santa Claus’s modern image, performed a similar rehabilitation on the Phrygian cap. To give his Santa a far-away but still benign look, he gave him a semi-Phrygian crossed with a camauro, the medieval clergyman’s cap. Subsequent artists exaggerated the peak and cocked it back, like a nightcap. Thus the red cap of revolution became the cartoon version of Christmas.