Since the first one was built in ancient Alexandria, lighthouses have helped humanity master the danger of the seas.

July 21, 2023

For those who dream big, there will be a government auction on Aug. 1 for two decommissioned lighthouses, one in Cleveland, Ohio, the other in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Calling these lighthouses “fixer-uppers,” however, hardly does justice to the challenge of converting them into livable

France’s Cordouan Lighthouse. GETTY IMAGES

homes. Lighthouses were built so man could fight nature, not sit back and enjoy it.

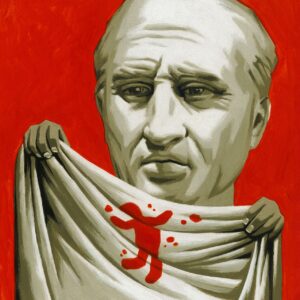

The Lighthouse of Alexandria, the earliest one recorded, was one of the ancient Seven Wonders of the World. An astonishing 300 feet tall or more, it was commissioned in 290 B.C. by Ptolemy I Soter, the founder of Egypt’s Ptolemaic dynasty, to guide ships into the harbor and keep them from the dangerous shoals surrounding the entrance. No word existed for lighthouse, hence it was called the Pharos of Alexandria, after the small islet on which it was located.

The Lighthouse did wonders for the Ptolemies’ reputation as the major power players in the region. The Romans implemented the same strategy on a massive scale. Emperor Trajan’s Torre de Hercules in A Coruña, in northwestern Spain, can still be visited. But after the empire’s collapse, its lighthouses were abandoned.

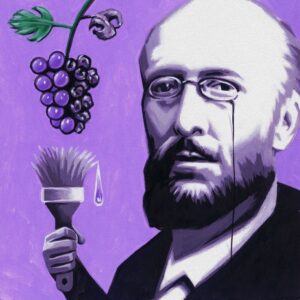

More than a thousand years passed before Europe again possessed the infrastructure and maritime capacity to need lighthouses, let alone build them. The contrasting approaches of France and England says much about the two cultures. The French regarded them as a government priority, resulting in such architectural masterpieces as Bordeaux’s Cordouan Lighthouse, commissioned by Henri III in 1584. The English entrusted theirs to Trinity House, a private charity, which led to inconsistent implementation. In 1707, poor lighthouse guidance contributed to the sinking of Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell’s fleet off the coast of the Scilly Isles, costing his and roughly 1,500 other lives.

Ida Lewis saved at least 18 people from drowning as the lighthouse keeper of Lime Rock in Newport, R.I.

In 1789, the U.S. adopted a third approach. Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, argued that federal oversight of lighthouses was an important symbol of the new government’s authority. Congress ordered the states to transfer control of their existing lighthouses to a new federal agency, the U.S. Lighthouse Establishment. But in the following decades Congress’s chief concern was cutting costs. America’s lighthouses were decades behind Europe’s in adopting the Fresnel lens, invented in France in 1822, which concentrated light into a powerful beam.

The U.S. had caught up by the time of the Civil War, but no amount engineering improvements could lessen the hardship and dangers involved in lighthouse-keeping. Isolation, accidents and deadly storms took their toll, yet it was one of the few government jobs open to women. Ida Lewis saved at least 18 people from drowning during her 54-year tenure of Lime Rock Station off Newport, R.I.

Starting in the early 1900s, there were moves to convert lighthouses to electricity. The days of the lighthouse keeper were numbered. Fortunately, when a Category 4 hurricane hit Galveston, Texas, on Sept. 8, 1900, its lighthouse station was still fully manned. The keeper, Henry C. Claiborne, managed to shelter 125 people in his tower before the storm surge engulfed the lower floors. Among them were the nine survivors of a stranded passenger train. Claiborne labored all night, manually rotating the lens after its mechanical parts became stuck. The lighthouse was a beacon of safety during the storm, and a beacon of hope afterward.

To own a lighthouse is to possess a piece of history, plus unrivaled views and not a neighbor in sight—a bargain whatever the price.