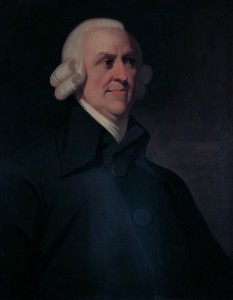

A few weeks ago, I spoke with Anne McElvoy for her BBC Radio series ‘British Liberalism: The Grand Tour’ about Adam Smith and the Whigs. I really enjoyed our conversation! Listen here: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b06r50wn

Press

Dr. Amanda Foreman explains the legacy of Pharaoh Hatshepsut, one of ten powerful women highlighted by the BBC for their political accomplishments:

‘. . . And the greatest of Egypt’s known ruling Queens was Hatshepsut. She came to power in the 15th century BC as the regent for her stepson Thutmose III; but it was how she ruled for over 2 decades that demonstrates her genius for government. Hatshepsut appropriated for herself the symbols of kingship… Famously, her statues depict her wearing the divine pharaonic beard. But just as important was how she concentrated on what Egypt did best. Building and trade. She organised the largest ever trade mission in her country’s history to the land of Punt. Her legacy was peace and prosperity. But even in Egypt there’s a sting in the tale. We don’t know why, but after her death, the next Pharaoh literally defaced Hatshepsut from the public record. In a sense, she represents the fate of so many women, not just in the ancient world, but throughout all of history.’

Read more here: http://www.bbc.co.uk/timelines/zp9qmp3

https://www.newstalk.com/listen_back/8/22887/10th_November_2015_-_Moncrieff_Part_4/

by Bridey Heing

In her BBC documentary and forthcoming book, historian and author Amanda Foreman uncovers the historical precedents that have erased women throughout human civilization.

History has long been a boys’ club, from the people being written about to the people writing the books. But historian and author Amanda Foreman is out to change that. With her recent four-part series on BBC aptly called “The Ascent of Woman,” she told the story of women in civilization in four parts. That, however, was just a warm-up. Her upcoming book, The World Made By Women: A History of Women From the Apple to the Pill, is the story of humanity from the perspective of the female half.

Here, Dr. Foreman shares her thoughts on the origins of patriarchy, the historical conspiracy responsible for silencing women, and the figures hidden in history whom we should all know more about.

By Helen Lewis

There’s a moment at the end of the film Suffragette that makes you gasp. Before the credits roll a simple list scrolls down the screen showing when women got the vote in countries around the world. It starts with New Zealand (1893) and ends with Saudi Arabia (2015), but the name that provokes the gasps is Switzerland. Gorgeous, snow-topped Switzerland, with its adorable cuckoo clocks and dubious attitude to Nazi gold, didn’t give women the vote until 1971.

For context, that’s after a man walked on the moon and the Beatles had broken up. “I don’t know what it is, but for some reason that seems to be the one that gets people,” agreed Suffragette’s writer Abi Morgan when I mentioned this to her. “I think it’s something about, you know, they make good chocolate – so surely they gave equality to women.”

Although I’m not discounting the chocolate connection, I have my own theory. Audiences are surprised because Switzerland is supposedly full of People Like Us: it’s an affluent western European nation, not a sand-blasted theocracy or a dirt-poor African dictatorship. And People Like Us believe in women’s equality. Don’t we?

By Gerard O’Donovan

Watching the final part of Amanda Foreman’s The Ascent of Woman (BBC Two) was a reminder of how powerful, inspiring and important television can be at its best. One of Foreman’s chief arguments has been that women have contributed as much to history as men but have rarely been accorded the credit for it.

And this final episode, which focused on a series of extraordinary but little known 19th- and 20th-century revolutionaries and campaigners, offered a formidable exposition of the extent to which so many women have, unforgivably, been written out of that history.

Literally so in the case of the French revolutionary Olympe de Gouges, who published her Declaration for the Rights of Women in 1791 and whose champions Foreman met and interviewed still, 200 years on, marching the streets of Paris to have her contributions fully recognised.

Time and again Foreman offered examples of revolutions in which the contributions of women were encouraged – until the subject of their own rights was broached. Perhaps most fascinatingly in the case of Alexandra Kollontai, an extraordinary firebrand who pushed feminism to the heart of the Bolshevik agenda during the Russian revolution – only to see it rolled back again by Stalin and her considerable achievements wiped from the record.

It was on the subject of forgotten heroines like this that the programme was at its most atmospheric, with Foreman joining candlelit memorial parades in Moscow, or interviewing Kollontai’s natural heirs, the members of Pussy Riot. But she was just as ardent, if not more so, in recalling the better known achievements of campaigners such as Millicent Fawcett, founder of Newnham College, Cambridge, and Margaret Sanger in America, whose tireless (and wonderfully fearless) campaigning for access to birth control eventually led to the development of the contraceptive pill in 1960 – a day when “women’s lives changed forever”.

There were times when Foreman could be accused of oversimplifying her argument. That there were political and social factors other than an unalloyed male desire to suppress the rise of women that perhaps contributed to the extinguishing of some of these feminist flames.

But to argue that would be to miss the point. What Foreman achieved in this episode was to distil the essence of the last two centuries of global striving for equality into the space of a single hour with enormous passion and erudition. Few who watched could be anything other than grateful for her efforts to redress the balance of history, or disagree with her conclusion that it is “vital for the future that we have a proper understanding of the past.”

Amanda Foreman’s documentary series The Ascent of Woman (Wednesdays, BBC2, 9pm) is full of ambition and lavishly produced – somehow the BBC budget has got her to Vietnam and China, India and Turkey, as well as to the door of the V&A in London. In tone, it harks back very deliberately to the glory days of Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation (1969) and Jacob Bronowski’s The Ascent of Man (1973) but with the crucial difference that barely a male face can be seen. During the third episode, when some pasty, bespectacled chap from the University of East Anglia was wheeled on to discuss the 16th-century obsession with witchcraft, I felt vaguely amazed, like I was watching a giraffe wander through my local park. Oh, how I cherish this almost total reliance on female expertise, one clever, learned woman following another, as if it were not at all unusual for women to be clever and learned (though it isn’t in life, most television still conspires to suggest otherwise).

Charlotte Hodgman is joined by historical author Amanda Foreman to discuss her new BBC2 TV series The Ascent of Woman.