Historically Speaking: Let Slip the Dogs, Birds and Donkeys of War

Animals have served human militaries with distinction since ancient times

August 5, 2021

Cher Ami, a carrier pigeon credited with rescuing a U.S. battalion from friendly fire in World War I, has been on display at the Smithsonian for more a century. The bird made news again this summer, when DNA testing revealed that the avian hero was a “he” and not—as two feature films, several novels and a host of poems depicted—a ”she.”

Cher Ami was one of more than 200,000 messenger pigeons Allied forces employed during the War. On Oct. 4, 1918, a battalion from the U.S. 77th Infantry Division in Verdun, northern France, was trapped behind enemy lines. The Germans had grown adept at shooting down any bird suspected of working for the other side. They struck Cher Ami in the chest and leg—but the pigeon still managed to make the perilous flight back to his loft with a message for U.S. headquarters.

Animals have played a crucial role in human warfare since ancient times. One of the earliest depictions of a war animal appears on the celebrated 4,500-year-old Sumerian box known as the Standard of Ur. One side shows scenes of war; the other, scenes of peace. On the war side, animals that are most probably onagers, a species of wild donkey, are shown dragging a chariot over the bodies of enemy soldiers.

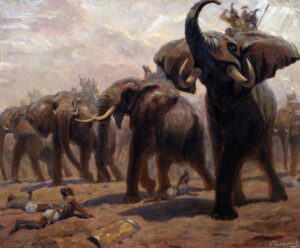

War elephants of Pyrrhus in a 20th century Russian painting

PHOTO: ALAMY

The two most feared war animals of the classical world were horses and elephants. Alexander the Great perfected the use of the former and introduced the latter after his foray into India in 327 BC. For a time, the elephant was the ultimate weapon of war. At the Battle of Heraclea in 280 B.C., a mere 20 of them helped Pyrrhus, king of Epirus—whose costly victories inspired the term “Pyrrhic victory”—rout an entire Roman army.

War animals didn’t have to be big to be effective, however. The Romans learned how to defeat elephants by exploiting their fear of pigs. In 198 B.C., the citizens of Hatra, near Mosul in modern Iraq, successfully fought off a Roman attack by pouring scorpions on the heads of the besiegers. Eight years later, the Carthaginian general Hannibal won a surprise naval victory against King Eumenes II of Pergamon by catapulting “snake bombs”—jars stuffed with poisonous snakes—onto his ships.

Ancient war animals often suffered extraordinary cruelty. When the Romans sent pigs to confront Pyrrhus’s army, they doused the animals in oil and set them on fire to make them more terrifying. Hannibal would get his elephants drunk and stab their legs to make them angry.

Counterintuitively, as warfare became more mechanized the need for animals increased. Artillery needed transporting; supplies, camps, and prisoners needed guarding. A favorite mascot or horse might be well treated: George Washington had Nelson, and Napoleon had Marengo. But the life of the common army animal was hard and short. The Civil War killed between one and three million horses, mules and donkeys.

According to the Imperial War Museum in Britain, some 16 million animals served during World War I, including canaries, dogs, bears and monkeys. Horses bore the brunt of the fighting, though, with as many as 8 million dying over the four years.

Dolphins and sea lions have conducted underwater surveillance for the U.S. Navy and helped to clear mines in the Persian Gulf. The U.S. Army relies on dogs to detect hidden IEDs, locate missing soldiers, and even fight when necessary. In 2016, four sniffer dogs serving in Afghanistan were awarded the K-9 Medal of Courage by the American Humane Association. As the troop withdrawal continues, the military’s four-legged warriors are coming home, too