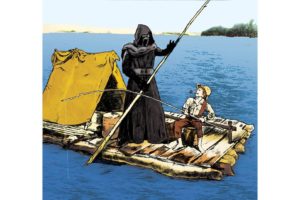

WSJ Historically Speaking: Kylo Ren, Meet Huck Finn: A History of Sequels and Their Heroes

The pedigree of sequels is as old as storytelling itself

ILLUSTRATION: RUTH GWILY

“Star Wars: The Last Jedi” may end up being the most successful movie sequel in the biggest sequel-driven franchise in the history of entertainment. That’s saying something, given Hollywood’s obsession with sequels, prequels, reboots and remakes. Although this year’s “Guardians of the Galaxy 2” was arguably better than the first, plenty of people—from critics to stand-up comedians—have wondered why in the world we needed a 29th “Godzilla,” an 11th “Pink Panther” or “The Godfather Part III.”

But sequels aren’t simply about chasing the money. They have a distinguished pedigree, as old as storytelling itself. Homer gets credit for popularizing the trend in the eighth century B.C., when he followed up “The Iliad” with “The Odyssey,” in which one of the relatively minor characters in the original story triumphs over sexy immortals, scary monsters and evil suitors of his faithful wife. Presumably with an eye to drawing in fans of the “Iliad,” Homer was sure to throw in a flashback about the Trojan horse.

Homer’s successors knew a good thing when they saw it. In 458 B.C., Aeschylus, the first of the great Greek dramatists, wrote his own sequel to “The Iliad,” a trilogy called “The Oresteia” that follows the often-bloody fates of the royal house of Agamemnon. More than 400 years later, the Latin poet Virgil penned a Roman-themed “Iliad” sequel, “The Aeneid,” which takes up the story from the point of view of the defeated Trojans.

The advent of printing in the 15th century made it easier to capitalize on a popular work. Roughly two decades after Shakespeare wrote “The Taming of the Shrew” around 1591, John Fletcher penned “The Woman’s Prize, or The Tamer Tam’d,” which reversed genders—with the women taming men. Shakespeare himself wrote sequels to some of his works, carrying his fat, irrepressible knight Falstaff through three plays.

By the Middle Ages, sequel activity had shifted focus. With “The Iliad” (like most of ancient Greek culture) virtually forgotten in Europe, tales about doomed lovers and Christian heroes, such as the legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, took the place of Homeric epics in the public imagination. A whole industry of Camelot sequels grew up around major and even minor characters of the story.

Eight hundred miles away in Madrid, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra countered an unauthorized sequel to his “Don Quixote” with his own sequel. In it, many of the characters have read Cervantes’ first part, Don Quixote himself is outraged by the plot of the fake sequel and Cervantes frequently ridicules the sequel writer.

Other authors had less success defending their creations. Jonathan Swift, author of “Gulliver’s Travels” (1726), was helpless when his own publisher immediately cashed in on the book’s success with several anonymous sequels, including “Memoirs of the Court of Lilliput.”

European audiences were not the only ones to yearn for sequels to favorite books. The oldest of China’s four classical novels, “Water Margin,” concerning a group of heroic outlaws, was completed sometime before the 17th century and spawned sequels that became classics in themselves. In late 19th-century America, Mark Twain struck gold twice with “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” followed by “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” But few people have heard of the second or third sequels: “Tom Sawyer Abroad” and “Tom Sawyer, Detective.”