WSJ Historically Speaking: The Ancient Magic of Mistletoe

The plant’s odyssey from a Greek festival to a role in the works of Dickens and Trollope

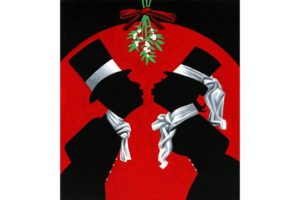

ILLUSTRATION: THOMAS FUCHS

Is mistletoe naughty or nice? The No. 1 hit single for Christmas 1952 was young Jimmy Boyd warbling how he caught “mommy kissing Santa Claus underneath the mistletoe last night.” It may very well have been daddy in costume—but, if not, that would make mistletoe very naughty indeed. For this plant, that would be par for the course.

Mistletoe, in its various species, is found all over the world and has played a part in fertility rituals for thousands of years. The plant’s ability to live off other trees—it’s a parasite—and remain evergreen even in the dead of winter awed the earliest agricultural societies. Mistletoe became a go-to plant for sacred rites and poetic inspiration.

Kissing under the mistletoe may have begun with the Greeks’ Kronia agricultural festival. Its Roman successor, the Saturnalia, combined licentious behavior with mistletoe. The naturalist Pliny the Elder, who died in A.D. 79, noticed to his surprise that mistletoe was just as sacred, if not more, to the Druids of Gaul. Its growth on certain oak trees, which the Druids believed to possess magical powers, spurred them to use mistletoe in ritual sacrifices and medicinal potions to cure ailments such as infertility.

Mistletoe’s mystical properties also earned it a starring role in the 13th-century Old Norse collection of mythical tales known as the Prose Edda. Here mistletoe becomes a deadly weapon in the form of an arrow that kills the sun-god Baldur. His mother Frigga, the goddess of love and marriage, weeps tears that turn into white mistletoe berries. In some versions, this brings Baldur back to life, carrying faint echoes of the reincarnation myths of ancient Mesopotamia. Either way, Frigga declares mistletoe to be the symbol of peace and love.

Beliefs about mistletoe’s powers managed to survive the Catholic Church’s official disapproval for all things pagan. People used the plant as a totem to scare away trolls, thwart witchcraft, prevent fires and bring about reconciliations. But such superstitions fizzled out in the wake of the Enlightenment.

In Britain, mistletoe displays continued to be a Yuletide custom, but only as a symbol for Nature’s power over death, and only in houses, never in churches. No one knows whether it was renewed interest in Greek or Celtic culture that brought the kissing ritual back into the equation. But its sudden popularity is attested by the number of 18th-century prints showing high jinks in servants’ halls at Christ

mas time.

Puritan-influenced America was slow to follow. Historically it was wary of Christmas rituals: During the 17th century, celebrating Christmas in Boston had carried a five-shilling fine. When Americans finally accepted mistletoe, literature led the way. Washington Irving’s hugely influential 1820 ”The Sketch Book” endearingly described a “traditional” English Christmas—mistletoe, servant girls and kissing included.

Back in England, Charles Dickens brought mistletoe from below stairs to the parlor in “The Pickwick Papers” (1837) and “A Christmas Carol” (1843). A couple of decades later, Anthony Trollope wrote a romantic short story, aptly called “The Mistletoe Bough,” which ends with a kiss under the plant. Its rehabilitation was complete. Every 19th-century household displayed a sprig of mistletoe at Christmas time—respectability and stolen kisses being a Victorian speciality.

Nowadays, hanging mistletoe has become a quaint tradition rather than a signal to cross over to the wild side. Yet there’s still magic in the leaves. Just close your eyes and wish.