Winston Churchill made the term famous, but ideological rivalries have driven geopolitics since Athens and Sparta.

February 25, 2021

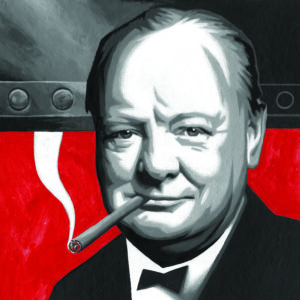

It was an unseasonably springlike day on March 5, 1946, when Winston Churchill visited Fulton, Missouri. The former British Prime Minister was ostensibly there to receive an honorary degree from Westminster College. But Churchill’s real purpose in coming was to urge the U.S. to form an alliance with Britain to keep the Soviet Union from expanding any further. Speaking before an august audience that included President Harry S. Truman, Churchill declared: “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the continent.”

ILLUSTRATION: THOMAS FUCHS

Churchill wasn’t the first person to employ the phrase “iron curtain” as a political metaphor. Originally a theatrical term for the safety barrier between the stage and the audience, by the early 20th century it was being used to mean a barrier between opposing powers. Nevertheless, “iron curtain” became indelibly associated with Churchill and with the defense of freedom and democracy.

This was a modern expression of an idea first articulated by the ancient Greeks: that political beliefs are worth defending. In the winter of 431-30 B.C., the Athenians were staggering under a devastating plague while simultaneously fighting Sparta in the Peloponnesian War. The stakes couldn’t have been higher when the great statesman Pericles used a speech commemorating the war dead to define the struggle in terms that every Athenian would understand.

As reported by the historian Thucydides, Pericles told his compatriots that the fight wasn’t for more land, trade or treasure; it was for democracy pure and simple. Athens was special because its government existed “for the many instead of the few,” guaranteeing “equal justice to all.” No other regime, and certainly not the Spartans, could make the same claim.

Pericles died the following year, and Athens eventually went down in defeat in 404 B.C. But the idea that fighting for one’s country meant defending a political ideal continued to be influential. According to the 2nd-century Roman historian Cassius Dio, the Empire had to make war on the “lawless and godless” tribes living outside its borders. Fortifications such as Hadrian’s Wall in northern England weren’t just defensive measures but political statements: Inside bloomed civilization, outside lurked savagery.

The Great Wall of China, begun in 220 B.C. by Emperor Qin Shi Huang, had a similar function. In addition to keeping out the nomadic populations in the Mongolian plains, the wall symbolized the unity of the country under imperial rule and the Confucian belief system that supported it. Successive dynasties continued to fortify the Great Wall until the mid-17th century.

During the Napoleonic Wars, the British considered themselves to be fighting for democracy against dictatorship, like the ancient Athenians. In 1806, Napoleon instigated the Continental System, an economic blockade intended to cut off Britain from trading with France’s European allies and conquests. But the attack on free trade only strengthened British determination.

A similar resolve among the NATO allies led to the collapse of the Iron Curtain in 1991, when the Soviet Union was dissolved and withdrew its armies from Eastern Europe. As Churchill had predicted, freedom and democracy is the ultimate shield against “war and tyranny.”