The cocktail was invented in the U.S., but it soon became a worldwide symbol of sophistication.

December 18, 2020

In 1887, the Chicago Tribune hailed the martini as the quintessential Christmas drink, reminding readers that it is “made of Vermouth, Booth’s Gin, and Angostura Bitters.” That remains the classic recipe, even though no one can say for certain who created it.

The journalist H.L. Mencken famously declared that the martini was “the only American invention as perfect as the sonnet,” and there are plenty of claimants to the title of inventor. The city of Martinez, Calif., insists the martini was first made there in 1849, for a miner who wanted to celebrate a gold strike with something “special.” Another origin story gives the credit to Jerry Thomas, the bartender of the Occidental Hotel in San Francisco, in 1867.

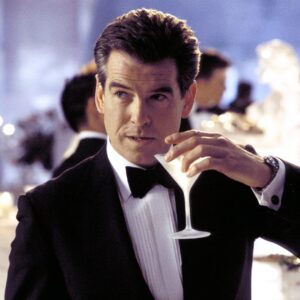

Actor Pierce Brosnan as James Bond, with his signature martini.

PHOTO: MGM/EVERETT COLLECTION

Of course, just as calculus was discovered simultaneously by Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz, the martini may have sprung from multiple cocktail shakers. What soon made it stand out from all other gin cocktails was its association with high society. The hero of “Burning Daylight,” Jack London’s 1910 novel about a gold-miner turned entrepreneur, drinks martinis to prove to himself and others that he has “arrived.” Ernest Hemingway paid tribute to the drink in his 1929 novel “A Farewell To Arms” with the immortal line, “I had never tasted anything so cool and clean. They made me feel civilized.”

Prohibition was a golden age for the martini. Its adaptability was a boon: Even the coarsest bathtub gin could be made palatable with the addition of vermouth and olive brine (a dirty martini), a pickled onion (Gibson), lemon (twist), lime cordial (gimlet) or extra vermouth (wet). President Franklin D. Roosevelt was so attached to the cocktail that he tried a little martini diplomacy on Stalin during the Yalta conference of 1945. Stalin could just about stand the taste but informed Roosevelt that the cold on the way down wasn’t to his liking at all.

The American love affair with the martini continued in Hollywood films like “All About Eve,” starring Bette Davis, which portrayed it as the epitome of glamour and sophistication. But change was coming. In Ian Fleming’s 1954 novel “Live and Let Die,” James Bond ordered a martini made with vodka instead of gin. Worse, two years later in “Diamonds are Forever,” Fleming described the drink as being “shaken and not stirred,” even though shaking weakens it. Then again, according to an analysis of Bond’s alcohol consumption published in the British Medical Journal in 2013, 007 sometimes downed the equivalent of 14 martinis in a 24-hour period, so his whole body would have been shaking.

American businessmen weren’t all that far behind. The three-martini lunch was a national pastime until business lunches ceased to be fully tax-deductible in the 1980s. Banished from meetings, the martini went back to its roots as a mixologists’ dream, reinventing itself as a ‘tini for all seasons.

The 1990s brought new varieties that even James Bond might have thought twice about, like the chocolate martini, made with creme de cacao, and the appletini, made with apple liqueur, cider or juice. Whatever your favorite, this holiday season let’s toast to feeling civilized.