Military leaders have been rulers since ancient times, but the U.S. has managed to keep them from becoming kings or dictators.

April 29, 2022

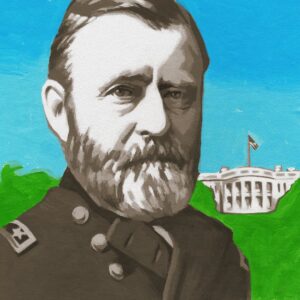

History has been kind to General Ulysses S. Grant, less so to President Grant. The hero of Appomattox, born 200 years ago this month, oversaw an administration beset by scandal. In his farewell address to Congress in 1876, Grant insisted lamely that his “failures have been errors of judgment, not of intent.”

Yet Grant’s presidency could as well be remembered for confirming the strength of American democracy at a perilous time. Emerging from the trauma of the Civil War, Americans sent a former general to the White House without fear of precipitating a military dictatorship. As with the separation of church and state, civilian control of the military is one of democracy’s hard-won successes.

In ancient times, the earliest kings were generals by definition. The Sumerian word for leader was “Lugal,” meaning “Big Man.” Initially, a Lugal was a temporary leader of a city-state during wartime. But by the 24th century B.C., Lugal had become synonymous with governor. The title wasn’t enough for Sargon the Great, c. 2334—2279 B.C., who called himself “Sharrukin,” or “True King,” in celebration of his subjugation of all Sumer’s city-states. Sargon’s empire lasted for three more generations.

In subsequent ancient societies, military and political power intertwined. The Athenians elected their generals, who could also be political leaders, as was the case for Pericles. Sparta was the opposite: The top Spartan generals inherited their positions. The Greek philosopher Aristotle described the Spartan monarchy—shared by two kings from two royal families—as a “kind of unlimited and perpetual generalship,” subject to some civic oversight by a 30-member council of elders.

ILLUSTRATION: THOMAS FUCHS

By contrast, ancient Rome was first a traditional monarchy whose kings were expected to fight with their armies, then a republic that prohibited actively serving generals from bringing their armies back from newly conquered territories into Italy, and finally a militarized autocracy led by a succession of generals-cum-emperors.

In later periods, boundaries between civil and military leadership blurred in much of the world. At the most extreme end, Japan’s warlords seized power in 1192, establishing the Shogunate, essentially a military dictatorship, and reducing the emperor to a mere figurehead until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. Napoleon trod a well-worn route in his trajectory from general to first consul, to first consul for life and finally emperor.

After defeating the British, General George Washington might have gone on to govern the new American republic in the manner of Rome’s Julius Caesar or England’s Oliver Cromwell. Instead, Washington chose to govern as a civilian and step down at the end of two terms, ensuring the transition to a new administration without military intervention. Astonished that a man would cling to his ideals rather than to power, King George III declared if Washington stayed true to his word, “he will be the greatest man in the world.”

The trust Americans have in their army is reflected in the tally of 12 former generals who have been U.S. presidents, from George Washington to Dwight D Eisenhower. President Grant may not have fulfilled the hopes of the people, but he kept the promise of the republic.