Modern medicine confirms what people have known for thousands of years: heartbreak is more than a metaphor.

September 30, 2023

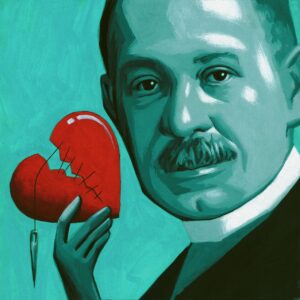

A mere generation ago, “heartbreak” was an overused literary metaphor but not an actual medical event. The first person to recognize it as a genuine condition was a Japanese cardiologist named Hikaru Sato. In 1990, Dr. Sato identified the curious case of a female patient who displayed the symptoms of a heart attack while testing negative for it. He named it “Takotsubo Syndrome” after noticing that the left ventricle of her heart changed shape during the episode to resemble a takotsubo, a traditional octopus-trap. A Japanese study in 2001 not only confirmed Sato’s identification of a sudden cardio event that mimics a heart attack but also highlighted the common factor of emotional distress in such patients. It had taken the medical profession 4,000 years to acknowledge what poets had been saying all along: Broken Heart Syndrome is real.

The heart has always been regarded as more than just a pump. The Sumerians of ancient Mesopotamia, now part of modern Iraq, understood it performed a physical function. But they also believed it was the source of all emotion, including love, happiness and despair. One of the first known references to “heartbreak” appears in a 17th century B.C. clay tablet containing a copy of “Atrahasis,” a Babylonian epic poem that parallels the Old Testament story of Noah’s Ark. The words “heart” and “break” are used to describe Atrahasis’s pain at being unable to save people from their imminent doom.

The heart also played a dual mind-body role in ancient Chinese medicine. There was a great emphasis on the importance of emotional regulation, since an enraged or greedy heart was believed to affect other organs. The philosopher Confucius used the heart as an analogy for the perfect relationship between the king and his people: Harmony in the latter and obedience from the former were both essential.

Heart surgeon Daniel Hale Williams. ILLUSTRATION BY THOMAS FUCHS

In the West, the early Catholic Church adopted a more top-down approach to the heart and its emotional problems. Submitting to Christ was the only treatment for what St. Augustine described as the discomfort of the unquiet heart. Even then, the avoidance of heart “pain” was not always possible. For the 16th-century Spanish saint Teresa of Avila, the agonizing sensation of being pierced in the heart was the necessary proof she had received God’s love.

By Shakespeare’s era, the idea of dying for love had become a cliché, but the deadly effects of heartbreak were accepted without question. Grief and anguish kill several of Shakespeare’s characters, including Lady Montague in “Romeo and Juliet,” King Lear, and Desdemona’s father in “Othello.” Shame drives Enobarbus to will his heart to stop in “Antony and Cleopatra”: “Throw my heart against the flint and hardness of my fault.”

London parish clerks continued to list grief as a cause of death until the 19th century, by which time advances in medical science had produced more mechanical explanations for life’s mysteries. In 1893, Daniel Hale Williams—founder of Provident Hospital in Chicago, the first Black-owned hospital in the U. S.—performed one of the earliest successful heart surgeries. He quite literally fixed the broken heart of a stabbing victim by sewing the pericardium or heart sac back together.

Nowadays, there are protocols for treating the coronary problem diagnosed by Dr. Sato. But although we can cure Broken Heart Syndrome, we still can’t cure a broken heart.