From the ancient Babylonians to Victorian England, the year’s end has been a time for self-reproach and general misery

The Wall Street Journal, January 3, 2019

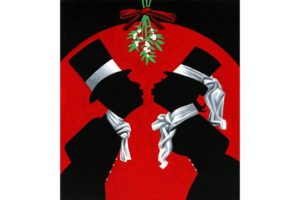

ILLUSTRATION: ALAN WITSCHONKE

I don’t look forward to New Year’s Eve. When the bells start to ring, it isn’t “Auld Lang Syne” I hear but echoes from the Anglican “Book of Common Prayer”: “We have left undone those things which we ought to have done; And we have done those things which we ought not to have done.”

At least I’m not alone in my annual dip into the waters of woe. Experiencing the sharp sting of regret around the New Year has a long pedigree. The ancient Babylonians required their kings to offer a ritual apology during the Akitu festival of New Year: The king would go down on his knees before an image of the god Marduk, beg his forgiveness, insist that he hadn’t sinned against the god himself and promise to do better next year. The rite ended with the high priest giving the royal cheek the hardest possible slap.

There are sufficient similarities between the Akitu festival and Yom Kippur, Judaism’s Day of Atonement—which takes place 10 days after the Jewish New Year—to suggest that there was likely a historical link between them. Yom Kippur, however, is about accepting responsibility, with the emphasis on owning up to sins committed rather than pointing out those omitted.

In Europe, the 14th-century Middle English poem “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” begins its strange tale on New Year’s Day. A green-skinned knight arrives at King Arthur’s Camelot and challenges the knights to strike at him, on the condition that he can return the blow in a year and a day. Sir Gawain reluctantly accepts the challenge, and embarks on a year filled with adventures. Although he ultimately survives his encounter with the Green Knight, Gawain ends up haunted by his moral lapses over the previous 12 months. For, he laments (in J.R.R. Tolkien’s elegant translation), “a man may cover his blemish, but unbind it he cannot.”

For a full dose of New Year’s misery, however, nothing beats the Victorians. “I wait its close, I court its gloom,” declared the poet Walter Savage Landor in “Mild Is the Parting Year.” Not to be outdone, William Wordsworth offered his “Lament of Mary Queen of Scots on the Eve of a New Year”: “Pondering that Time tonight will pass / The threshold of another year; /…My very moments are too full / Of hopelessness and fear.”

Fortunately, there is always Charles Dickens. In 1844, Dickens followed up the wildly successful “A Christmas Carol” with a slightly darker but still uplifting seasonal tale, “The Chimes.” Trotty Veck, an elderly messenger, takes stock of his life on New Year’s Eve and decides that he has been nothing but a burden on society. He resolves to kill himself, but the spirits of the church bells intervene, showing him a vision of what would happen to the people he loves.

Today, most Americans recognize this story as the basis of the bittersweet 1946 Frank Capra film “It’s a Wonderful Life.” As an antidote to New Year’s blues, George Bailey’s lesson holds true for everyone: “No man is a failure who has friends.”