The show turns 50 this month, but the idea that education can be entertaining goes back to ancient Greece.

The Wall Street Journal, November 21, 2019

“Sesame Street,” which first went on the air 50 years ago this month, is one of the most successful and cost-effective tools ever created for preparing preschool tots for the classroom. Now showing in 70 languages in more than 150 countries around the world, “Sesame Street” is that rare thing in a child’s life: truly educational entertainment.

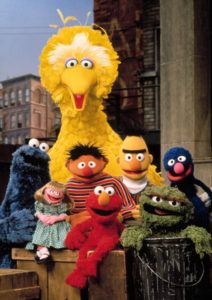

The Muppets of ‘Sesame Street’ in the 1993-94 season. PHOTO: EVERETT COLLECTION

Historically, those two words have rarely appeared together. In the 4th century B.C., Plato and Aristotle both agreed that children can learn through play. In “The Republic,” Plato went so far as to advise, “Do not use compulsion, but let early education be a sort of amusement.” Unfortunately, his advice failed to catch on.

In Europe during the Middle Ages, play and learning were almost diametrically opposed. Monks were in charge of boys’ education, which largely consisted of Latin grammar and religious teaching. (Girls learned domestic skills at home.) The invention of the printing press in 1440 helped spread literacy among young readers, but the works written for them weren’t exactly entertaining. A book like “A token for children: Being an exact account of the conversion, holy and exemplary lives, and joyful deaths of several young children,” by the 17th-centrury English Puritan James Janeway, surely didn’t follow Plato’s injunction to be amusing as well as instructional.

Social attitudes toward children’s entertainment changed considerably, however, in the wake of the English philosopher John Locke’s 1693 treatise “Some Thoughts Concerning Education.” Locke followed Plato’s line on education, writing, “I always have had a fancy that learning might be made a play and recreation to children.” The publisher John Newbery heeded Locke’s advice; in 1744, he published “A Little Pretty Pocket-Book Intended for the Instruction and Amusement of Little Master Tommy and Pretty Miss Polly,” which was sold along with a ball for boys and a pincushion for girls. In the introduction, Newbery promised parents and guardians that the book would not only make their children “strong, healthy, virtuous, wise” but also “happy.”

When it came to early children’s television in the U.S., however, “play and recreation” usually squeezed out educational content. Many popular shows existed primarily to sell toys and products: “Howdy Doody,” the pioneering puppet show that ran on NBC from 1947 to 1960, was sponsored by RCA to pitch color televisions. Parents became so indignant over the exploitation of their children by the TV industry that, in 1968, grass-roots activists started the nonprofit Action for Children’s Television, which petitioned the Federal Communications Commission to ban advertising on children’s programming.

This cultural mood led to the birth of “Sesame Street.” The show’s co-creators, Joan Ganz Cooney and Lloyd Morrisett, were particularly devoted to using TV to combat educational inequality in minority communities. They spent three years working with teachers, child psychologists and Jim Henson’s Muppets to get the right mix of education and entertainment. The pilot episode, broadcast on public television stations on Nov. 10, 1969, introduced the world to Big Bird, Bert and Ernie, Oscar the Grouch, and their cast of multiethnic friends and neighbors. “You’re gonna love it,” says one of the show’s human characters, Gordon, to his wife Sally in the first show’s opening lines. And we have.