This Thanksgiving, let’s spare a thought for the roughly 40 million turkeys whose destiny is inextricably linked to the fourth Thursday in November.

As a symbol of national pride and family values, the humble turkey has few rivals. But how did it edge out the competition to become the quintessential Thanksgiving dish?

Success was neither immediate nor assured. It isn’t clear whether turkey made it onto the menu at the original 1621 harvest-celebration meal shared among the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag. Wild turkeys were plentiful; the colonist leader William Bradford noted in his diary that “there was a great store” of them. But the only surviving letter about that meal refers to four men who went “a-fowling,” which could have meant anything from ducks to swans.

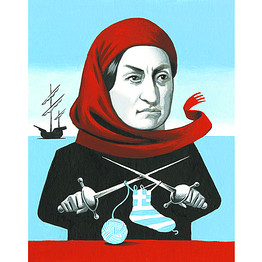

The tradition of Congress issuing a national Thanksgiving proclamation began in 1777, at around the same time that the Great Seal of the U.S. was being designed, and the turkey wasn’t a serious contender to be the symbol of America. The birds considered included the rooster, the dove and the eagle. In the end, the Great Seal committee accepted Charles Thomson’s 1782 suggestion of the bald eagle.

But two years later, Benjamin Franklin found himself wondering whether they had made a mistake: “I wish the Bald Eagle had not been chosen the Representative of our Country. He is a Bird of bad moral Character. He does not get his Living honestly…he is generally poor and often very lousy.” By contrast, Franklin wrote, the turkey was a “much more respectable bird…though a little vain and silly, a Bird of courage.”