Smithsonian Magazine: The Amazon Women: Is There Any Truth Behind the Myth?

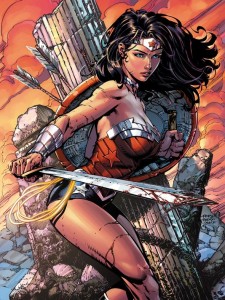

I loved watching the “Wonder Woman” TV series when I was a girl. I never wanted to dress like her—the idea of wearing a gold lamé bustier and star-spangled blue underwear all day seemed problematic—but the Amazonian princess was strong and resourceful, with a rope trick for every problem. She seemed to be speaking directly to me, urging, “Go find your own inner Amazonian.” When I read the news that Wonder Woman was going to be resurrected for a blockbuster movie in 2016, Batman vs. Superman, it made me excited—and anxious. Would the producers give her a role as fierce as her origins—and maybe some shoulder straps—or would she just be cartoon eye candy?

The fact that she isn’t even getting billing in the title makes me suspicious. It wouldn’t have pleased Wonder Woman’s creator either. “Wonder Woman is psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should, I believe, rule the world,” declared the psychologist and comic book writer William Moulton Marston, offering a proto-feminist vision that undoubtedly sounded quite radical in 1943. “Not even girls want to be girls so long as our feminine archetype lacks force, strength and power. Not wanting to be girls, they don’t want to be tender, submissive, peace-loving as good women are.”

Over the years, the writers at DC Comics softened Wonder Woman’s powers in ways that would have infuriated Marston. During the 1960s, she was hardly wondrous at all, less a heroic warrior than the tomboyish girl next-door. It was no longer clear whether she was meant to empower the girls or captivate the boys. But the core brand was still strong enough for Gloria Steinem to put her on the cover of the first newsstand issue of Ms. magazine in 1972—with the slogan “Wonder Woman for President.”

The creators of Wonder Woman had no interest in proving an actual link to the past. In some parts of the academic world, however, the historical existence of the Amazons, or any matriarchal society, has long been a raging issue. The origins of the debate can be traced back to a Swiss law professor and classical scholar named Johann Jakob Bachofen. In 1861 Bachofen published his radical thesis that the Amazons were not a myth but a fact. In his view, humanity started out under the rule of womankind and only switched to patriarchy at the dawn of civilization. Despite his admiration for the earth-mother women/priestesses who once held sway, Bachofen believed that the domination of men was a necessary step toward progress. Women “only know of the physical life,” he wrote. “The triumph of patriarchy brings with it the liberation of the spirit from the manifestations of nature.”

It comes as no surprise that the composer Richard Wagner was enthralled by Bachofen’s writings. Brünnhilde and her fellow Valkyries could be easily mistaken for flying Amazons. But Bachofen’s influence went far beyond the Ring Cycle. Starting with Friedrich Engels, Bachofen inspired generations of Marxist and feminist theorists to write wistfully of a pre-patriarchal age when the evils of class, property and war were unknown. As Engels memorably put it: “The overthrow of mother-right was the world historical defeat of the female sex. The man took command in the home also; the woman was degraded and reduced to servitude; she became the slave of his lust and a mere instrument for the production of children.”

There was, however, one major problem with the Bachofen-inspired theory of matriarchy: There was not a shred of physical evidence to support it. In the 20th century, one school of thought claimed that the real Amazons were probably beardless “bow-toting Mongoloids” mistaken for women by the Greeks. Another insisted that they were simply a propaganda tool used by the Athenians during times of political stress. The only theorists who remained relatively unfazed by the debates swirling through academia were the Freudians, for whom the idea of the Amazons was far more interesting in the abstract than in a pottery fragment or arrowhead. The Amazonian myths appeared to hold the key to the innermost neuroses of the Athenian male. All those women sitting astride their horses, for example—surely the animal was nothing but a phallus substitute. As for their violent death in tale after tale, this was obviously an expression of unresolved sexual conflict.

Myth or fact, symbol or neurosis, none of the theories adequately explained the origins of the Amazons. If these warrior women were a figment of Greek imagination, there still remained the unanswered question of who or what had been the inspiration for such an elaborate fiction. Their very name was a puzzle that mystified the ancient Greeks. They searched for clues to its origins by analyzing the etymology of Amazones, the Greek for Amazon. The most popular explanation claimed that Amazones was a derivation of a, “without,” and mazos, “breasts”; another explanation suggested ama-zoosai, meaning “living together,” or possibly ama-zoonais, “with girdles.” The idea that Amazons cut or cauterized their right breasts in order to have better bow control offered a kind of savage plausibility that appealed to the Greeks.

The eighth-century B.C. poet Homer was the first to mention the existence of the Amazons. In the Iliad—which is set 500 years earlier, during the Bronze or Heroic Age—Homer referred to them somewhat cursorily as Amazons antianeirai, an ambiguous term that has resulted in many different translations, from “antagonistic to men” to “the equal of men.” In any case, these women were considered worthy enough opponents for Homer’s male characters to be able to boast of killing them—without looking like cowardly bullies.

Future generations of poets went further and gave the Amazons a fighting role in the fall of Troy—on the side of the Trojans. Arktinos of Miletus added a doomed romance, describing how the Greek Achilles killed the Amazonian queen Penthesilea in hand-to-hand combat, only to fall instantly in love with her as her helmet slipped to reveal the beautiful face beneath. From then on, the Amazons played an indispensable role in the foundation legends of Athens. Hercules, for example, last of the mortals to become a god, fulfills his ninth labor by taking the magic girdle from the Amazon queen Hippolyta.

By the mid-sixth century B.C., the foundation of Athens and the defeat of the Amazons had become inextricably linked, as had the notion of democracy and the subjugation of women. The Hercules versus the Amazons myth was adapted to include Theseus, whom the Athenians venerated as the unifier of ancient Greece. In the new version, the Amazons came storming after Theseus and attacked the city in a battle known as the Attic War. It was apparently a close-run thing. According to the first century A.D. Greek historian Plutarch, the Amazons “were no trivial nor womanish enterprise for Theseus. For they would not have pitched their camp within the city, nor fought hand-to-hand battles in the neighborhood of the Pynx and the Museum, had they not mastered the surrounding country and approached the city with impunity.” As ever, though, Athenian bravery saved the day.

The first pictorial representations of Greek heroes fighting scantily clad Amazons began to appear on ceramics around the sixth century B.C. The idea quickly caught on and soon “amazonomachy,” as the motif is called (meaning Amazon battle), could be found everywhere: on jewelry, friezes, household items and, of course, pottery. It became a ubiquitous trope in Greek culture, just like vampires are today, perfectly blending the allure of sex with the frisson of danger. The one substantial difference between the depictions of Amazons in art and in poetry was the breasts. Greek artists balked at presenting anything less than physical perfection.

The more important the Amazons became to Athenian national identity, the more the Greeks searched for evidence of their vanquished foe. The fifth century B.C. historian Herodotus did his best to fill in the missing gaps. The “father of history,” as he is known, located the Amazonian capital as Themiscyra, a fortified city on the banks of the Thermodon River near the coast of the Black Sea in what is now northern Turkey. The women divided their time between pillaging expeditions as far afield as Persia and, closer to home, founding such famous towns as Smyrna, Ephesus, Sinope and Paphos. Procreation was confined to an annual event with a neighboring tribe. Baby boys were sent back to their fathers, while the girls were trained to become warriors. An encounter with the Greeks at the Battle of Thermodon ended this idyllic existence. Three shiploads of captured Amazons ran aground near Scythia, on the southern coast of the Black Sea. At first, the Amazons and the Scythians were braced to fight each other. But love indeed conquered all and the two groups eventually intermarried. Their descendants became nomads, trekking northeast into the steppes where they founded a new race of Scythians called the Sauromatians. “The women of the Sauromatae have continued from that day to the present,” wrote Herodotus, “to observe their ancient customs, frequently hunting on horseback with their husbands…in war taking the field and wearing the very same dress as the men….Their marriage law lays it down, that no girl shall wed until she has killed a man in battle.”

The trail of the Amazons nearly went cold after Herodotus. Until, that is, the early 1990s when a joint U.S.-Russian team of archaeologists made an extraordinary discovery while excavating 2,000-year-old burial mounds—known as kurgans—outside Pokrovka, a remote Russian outpost in the southern Ural Steppes near the Kazakhstan border. There, they found over 150 graves belonging to the Sauromatians and their descendants, the Sarmatians. Among the burials of “ordinary women,” the researchers uncovered evidence of women who were anything but ordinary. There were graves of warrior women who had been buried with their weapons. One young female, bowlegged from constant riding, lay with an iron dagger on her left side and a quiver containing 40 bronze-tipped arrows on her right. The skeleton of another female still had a bent arrowhead embedded in the cavity. Nor was it merely the presence of wounds and daggers that amazed the archaeologists. On average, the weapon-bearing females measured 5 feet 6 inches, making them preternaturally tall for their time.

Finally, here was evidence of the women warriors that could have inspired the Amazon myths. In recent years, a combination of new archaeological finds and a reappraisal of older discoveries has confirmed that Pokrovka was no anomaly. Though clearly not a matriarchal society, the ancient nomadic peoples of the steppes lived within a social order that was far more flexible and fluid than the polis of their Athenian contemporaries.

To the Greeks, the Scythian women must have seemed like incredible aberrations, ghastly even. To us, their graves provide an insight into the lives of the world beyond the Adriatic. Strong, resourceful and brave, these warrior women offer another reason for girls “to want to be girls” without the need of a mythical Wonder Woman.