Ancient Jews and Christians observed a day of rest, but not until the 20th century did workers get two days a week to do as they pleased.

April 1, 2021

Last month the Spanish government agreed to a pilot program for experimenting with a four-day working week. Before the pandemic, such a proposal would have seemed impossible—but then, so was the idea of working from home for months on end, with no clear downtime and no in-person schooling to keep the children occupied.

In ancient times, a week meant different things to different cultures. The Egyptians used sets of 10 days called decans; there were no official days off except for the craftsmen working on royal tombs and temples, who were allowed two days out of every 10. The Romans tried an eight-day cycle, with the eighth set aside as a market day. The Babylonians regarded the number seven as having divine properties and applied it whenever possible: There were seven celestial bodies, seven nights of each lunar phase and seven days of the week.

A day of leisure in Newport Beach, Calif., 1928. PHOTO: DICK WHITTINGTON STUDIO/CORBIS/GETTY IMAGES

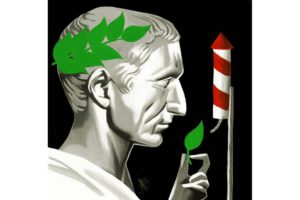

The ancient Jews, who also used a seven-day week, were the first to mandate a Sabbath or rest day, on Saturday, for all people regardless of rank or occupation. In 321 A.D., the Roman emperor Constantine integrated the Judeo-Christian Sabbath into the Julian calendar, but mindful of pagan sensibilities, he chose Sunday, the day of the god Sol, for rest and worship.

Constantine’s tinkering was the last change to the Western workweek for more than a millennia. The authorities saw no reason to allow the lower orders more than one day off a week, but they couldn’t stop them from taking matters into their own hands. By the early 18th century, the custom of “keeping Saint Monday”—that is, taking the day to recover from the Sunday hangover—had become firmly entrenched among the working classes in America and Britain.

Partly out of desperation, British factory owners began offering workers a half-day off on Saturday in return for a full day’s work on Monday. Rail companies supported the campaign with cheap-rate Saturday excursions. By the late 1870s, the term “weekend” had become so popular that even the British aristocracy started using it. For them however, the weekend began on Saturday and ended on Monday night.

American workers weren’t so fortunate. In 1908, a few New England mill owners granted workers Saturdays and Sundays off because of their large number of Jewish employees. Few other businesses followed suit until 1922, when Malcolm Gray, owner of the Rochester Can Company in upstate New York, decided to give a five-day week to his workers as a Christmas gift. The subsequent uptick in productivity was sufficiently impressive to convince Henry Ford to try the same experiment in 1926 at the Ford Motor Company. Ford’s success made the rest of the country take notice.

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union was moving in the other direction. In 1929, Joseph Stalin introduced the continuous week, which required 80% of the population to be working on any given day. It was so unpopular that the system was abandoned in 1940, the same year that the five-day workweek became law in the U.S. under the Fair Labor Standards Act. The battle for the weekend had been won at last. Now let the battle for the four-day week begin.