U.S. antiterror efforts have cost nearly $6 trillion since the 9/11 attacks. Earlier governments from the ancient Greeks to Napoleon have had to get creative to finance their fights

The successful operation against Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is a bright spot in the war on terror that the U.S. declared in response to the attacks of 9/11. The financial costs of this long war have been enormous: nearly $6 trillion to date, according to a recent report by the Watson Institute of International and Public Affairs at Brown University, which took into account not just the defense budget but other major costs, like medical and disability care, homeland security and debt.

ILLUSTRATION: THOMAS FUCHS

War financing has come a long way since the ancient Greeks formed the Delian League in 478 B.C., which required each member state to contribute an agreed amount of money each year, rather than troops,. With the League’s financial backing, Athens became the Greek world’s first military superpower—at least until the Spartans, helped by the Persians, built up their naval fleet with tribute payments extracted from dependent states.

The Romans maintained their armies through tributes and taxes until the Punic Wars—three lengthy conflicts between 264 and 146 B.C.—proved so costly that the government turned to debasing the coinage in an attempt to increase the money supply. The result was runaway inflation and eventually a sovereign debt crisis during the Social War a half-century later between Rome and several breakaway Italian cities. The government ended up defaulting in 86 B.C., sealing the demise of the ailing Roman Republic.

After the fall of Rome in the late fifth century, wars in Europe were generally financed by plunder and other haphazard means. William the Conqueror financed the Norman invasion of England in 1066 the ancient Roman way, by debasing his currency. He learned his lesson and paid for all subsequent operations out of tax receipts, which stabilized the English monetary system and established a new model for financing war.

Taxation worked until European wars became too expensive for state treasuries to fund alone. Rulers then resorted to a number of different methods. During the 16th century, Philip I of Spain turned to the banking houses of Genoa to raise the money for his Armada invasion fleet against England. Seizing the opportunity, Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth I’s chief spymaster, sent agents to Genoa with orders to use all legal means to sabotage and delay the payment of Philip’s bills of credit. The operation bought England a crucial extra year of preparation.

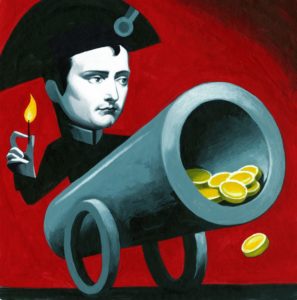

In his own financial preparations to fight England, Napoleon had better luck than Philip I: In 1803 he was able to raise a war chest of over $11 million in cash by selling the Louisiana Territory to the U.S.

Napoleon was unusual in having a valuable asset to offload. By the time the American Civil War broke out in 1861, governments had become reliant on a combination of taxation, printing money or borrowing to pay for war. But the U.S. lacked a regulated banking system since President Andrew Jackson’s dismantling of the Second Bank of the United States in the 1830s. The South resorted to printing paper money, which depreciated dramatically. The North could afford to be more innovative. In 1862 the financier Jay Cooke invented the war bond. This was marketed with great success to ordinary citizens. At the war’s end, the bonds had covered two-thirds of the North’s costs.

Incurring debt is still how the U.S. funds its wars. It has helped to shield the country from the full financial effects of its prolonged conflicts. But in the future it is worth remembering President Calvin Coolidge’s warning: “In any modern campaign the dollars are the shock troops…. A country loaded with debt is devoid of the first line of defense.”