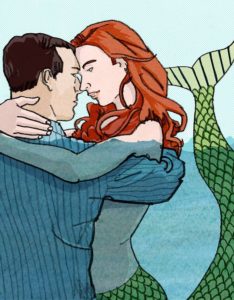

ILLUSTRATON: DANIEL ZALKUS

‘The Shape of Water,’ the best-picture winner, extends a tradition of ancient tales of these water creatures and their dealings with humans

Popular culture is enamored with mermaids. This year’s Best Picture Oscar winner, Guillermo del Toro’s “The Shape of Water,” about a lonely mute woman and a captured amphibious man, is a new take on an old theme. “The Little Mermaid,” Disney ’senormously successful 1989 animated film, was based on the Hans Christian Andersen story of the same name, and it was turned into a Broadway musical, which even now is still being staged across the country.

The fascination with mermythology began with the ancient Greeks. In the beginning, mermen were few and far between. As for mermaids, they were simply members of a large chorus of female sea creatures that included the benign Nereids, the sea-nymph daughters of the sea god Nereus, and the Sirens, whose singing led sailors to their doom—a fate Odysseus barely escapes in Homer’s epic “The Odyssey.”

Over the centuries, the innocuous mermaid became interchangeable with the deadly sirens. They led Scottish sailors to their deaths in one of the variations of the anonymous poem “Sir Patrick Spens,” probably written in the 15th century: “Then up it raise the mermaiden, / Wi the comb an glass in her hand: / ‘Here’s a health to you, my merrie young men, / For you never will see dry land.’”

In pictures, mermaids endlessly combed their hair while sitting semi-naked on the rocks, lying in wait for seafarers. During the Elizabethan era, a “mermaid” was a euphemism for a prostitute. Poets and artists used them to link feminine sexuality with eternal damnation.

But in other tales, the original, more innocent idea of a mermaid persisted. Andersen’s 1837 story followed an old literary tradition of a “virtuous” mermaid hoping to redeem herself through human love.

Andersen purposely broke with the old tales. As he acknowledged to a friend, his fishy heroine would “follow a more natural, more divine path” that depended on her own actions rather than that of “an alien creature.” Egged on by her sisters to murder the prince whom she loves and return to her mermaid existence, she chooses death instead—a sacrifice that earns her the right to a soul, something that mermaids were said to lack.

Richard Wagner’s version of mermaids—the Rhine maidens who guard the treasure of “Das Rheingold”—also bucked the “temptress” cliché. While these maidens could be cruel, they gave valuable advice later in the “Ring” cycle.

The cultural rehabilitation of mermaids gained steam in the 20th century. In T.S. Eliot’s 1915 poem, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” their erotic power becomes a symbol of release from stifling respectability. The sad protagonist laments, “I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each. / I do not think that they will sing to me.” By 1984, when a gorgeous mermaid (Daryl Hannah) fell in love with a nerdy man ( Tom Hanks ) in the film comedy “Splash,” audiences were ready to accept that mermaids might offer a liberating alternative to society’s hang-ups, and that humans themselves are the obstacle to perfect happiness, not female sexuality.

What makes “The Shape of Water” unusual is that a scaly male, not a sexy mermaid, is the object of affection to be rescued. Andersen probably wouldn’t recognize his Little Mermaid in Mr. del Toro’s nameless, male amphibian, yet the two tales are mirror images of the same fantasy: Love conquers all.