The same ease of transport enabled British immigrants to avoid the fetid slums of New York and seek a new life in any of the thirty-four states and seven territories of America. There were Englishmen in the New England mills and on the Texas homesteads, Cornishmen in the Wisconsin lead minds, Welshmen in the Ohio collieries, and Scots in the Vermont Quarries and Carolina plantations. Unlike the Germans, Poles, Italians and Irish, who clustered in conspicuous communities in the North, the British tended to integrate very quickly. In the North their sentiments were largely pro-Union and vehemently anti-slavery, while below the Mason-Dixon line they sided with the majority in favour of secession. During his tour of the South, the Times correspondent, Sir William Russell, was surprised to see what a difference a few miles could make to the moral opinions of his compatriots. Among the most articulate defenders of slavery were some of the, ‘British residents, English, Irish and Scotch, who have settled here for trading purposes, and who are frequently slave-holders. These men have no state rights to uphold, but they are convinced of the excellence of things as they are…’

As the bickering between the North and South turned into bitterness, southerners took great satisfaction in pointing out that the world depended on its cotton. In 1858 the loud-voiced Senator from South Carolina, James H. Hammond, spelled it out to a silent Congress. No one dared say no to the South, he declared, not even mighty Britain. Deprived of cotton she, ‘would topple headlong and carry the whole civilized world with her. No, you dare not make war on cotton. No power on earth dares make war on it. Cotton is King.’

The war officially began on 12 April 1861, when the South Carolina artillery pounded the tiny Federal garrison out of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbour. Understandably, news of the engagement roused secessionism to a fever pitch among southerners. They were absolutely convinced of two things: that the North did not have the stomach for a fight, and that Britain would recognize their independence. They were wrong on both counts.

London remained loudly silent. The government was inclined to recognise the South, but not at the cost of becoming involved in the war. It feared losing southern cotton, and yet did not wish to prop-up a slave economy. The British press, however, suffered no such doubts. Editorials applauded Lincoln and denounced the South as ‘bullies’. The rush of volunteers in the free states added excitement to the reports crossing the Atlantic. These were heady although precarious times. The Secretary of State, William H. Seward, bluntly told Russell, that the North would fight Britain too, if she attempted to interfere. ‘We shall not shrink from it,’ he warned. ‘A contest between the Great Britain and the United States would wrap the world in fire.’

When Britain revealed her hand in May 1861, North and South were equally enraged. Queen Victoria issued a Proclamation of Strict Neutrality. This was far less than what the South had expected, and far more than the North would tolerate. Strict Neutrality recognised the South as a legitimate fighting entity, but also the North’s right to blockade her ports. Britain considered this a fair compromise. But the North considered it tantamount to a recognition of Southern independence. A leading Northern Senator pronounced it ‘the most hateful act of English history since the time of Charles II’.

In theory the Proclamation prohibited British subjects from enlisting in either military service, from violating the Northern blockade, and from fitting out or equipping Union or Confederate vessels for warlike purposes. In practice, people did exactly as they pleased. In the first months of the war, officers, soldiers and ordinary civilians left in droves for America. They joined a mass exodus that included thousands of Germans, Irish and other Europeans. Later, as the Northern blockade increased, Britain also furnished an unofficial navy of blockade runners. ‘Firm after firm,’ recalled an English blockade runner, ‘with an entirely clear conscience, set about endeavouring to recoup itself for the loss of legitimate trade by the high profits to be made out of successful evasions of the Federal cruisers.’ At the height of the war, between 1862-4, Liverpool exhibited an energy and spirit not seen since the bustling days of the Slave Tra de. Seamen who supported the Confederacy scratched the figure of a turkey into the lintels of their houses, a few of which survive to this day.

Altogether, some 50,000 British men and women participated in the war. The South, already disappointed by Britain’s refusal to grant recognition, deeply resented the influx of foreigners who filled the ranks of the Union army. However, as we shall see, it too attracted a sizable number. Moreover, it was the grit and tenacity of the British blockade runners which enabled the Confederate army to enter the field with more than bowie knives. The problem for the South was not a lack of rifles but the dwindling supply of men.

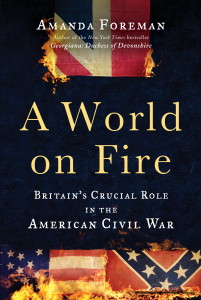

The British involvement in the Civil War has always been a sensitive subject. At the time, Northerners accused Britain of complicity; Southerners, of betrayal. The bitterness engendered by the war no longer taints Anglo-American relations. However, grudging acceptance has come at the cost of historical amnesia. The British who fought alongside Union and Confederate soldiers have disappeared from the picture. With them, the world they inhabited, an Anglo-American world bound by shared ideals, shared dreams and shared kin, has disappeared too.

As cousins by culture and yet strangers by nature, these British adventurers are unrivaled historical witnesses. Moreover, their perspective as both the parent and rival of American civilisation, their experiences of immigration and integration, their understanding of the outsider’s struggle, makes them a talisman for the present. There has never been a book about the bloody pas-de-deux between these closest of strangers.

Historians have, of course, written diplomatic histories of the war; made studies of foreign volunteers; exposed the extent of Federal and Confederate espionage in Britain, described the Confederate naval operations in England, and examined the international reporting of the conflict. But no one – understandably, given the breadth and depth of the research required – has ever drawn all the facets together into a multi-stranded narrative of the Anglo-American world during the Civil War.

A World on Fire’ began as a study of the British volunteers. But eight years of research revealed a vast cyclorama, an immersion of humanity, that demanded its own epic telling. The British volunteers provided a wealth of unique histories. But it was only by placing each one within and alongside the biographies of their neighbour, their enemy, their army, their government, and ultimately the war itself, did the many and the one achieve a synthesis of meaning.

Winner of the Fletcher Pratt Award for Civil War History

Winner of the Fletcher Pratt Award for Civil War History