In April 1896, a flock of American passenger pigeons was discovered nesting in a forest outside Bowling Green, Ohio. Once the most ubiquitous bird in North America, the passenger pigeon had shrunk from countless billions to this single of flock of 250,000. News of the find was telegraphed across the country, drawing hundreds of visitors to the area.

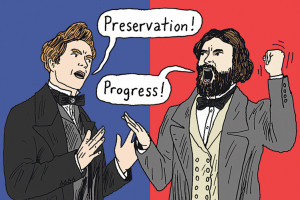

By this time, the great bison—a powerful symbol of frontier America—had dwindled from a population of tens of millions to just a few hundred, all in zoos or reservations. Determined to prevent a similar fate for the passenger pigeon, several states had already enacted hunting bans. Seeing the birds gave conservationists hope that the restrictions were working.

Unfortunately, the visitors to Bowling Green weren’t bird watchers but hunters, and Ohio had no such protective laws. They killed the entire flock in a day. Afterward, the train taking the carcasses to sell in New York City derailed, leaving them to rot in a ravine. Eighteen years later, the lone survivor of the species—a female bird named Martha, after George Washington’s wife—died in a cage in the Cincinnati zoo.