Today’s DNA techniques are just the latest addition to a toolkit used by detectives since ancient times.

May 5, 2023

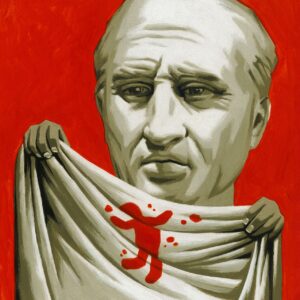

The practice of forensic science, the critical examination of crime scenes, existed long before it had a name. The 1st-century A.D. Roman jurist Quintilian argued that evidence was not the same as proof unless supported by sound method and reasoning. Nothing should be taken at face value: Even blood stains on a toga, he pointed out, could be the result of a nosebleed or a messy religious sacrifice rather than a murder.

In 6th-century Byzantium, the Justinian Law Code allowed doctors to serve as expert witnesses, recognizing that murder cases required specialized knowledge. In Song Dynasty China, coroners were guided by Song Ci, a 13th-century judge who wrote “The Washing Away of Wrongs,” a comprehensive handbook on criminology and forensic science. Using old case studies, Song provided step-by-step instructions on how to tell if a drowned person had been alive before hitting the water and whether blowflies could be attracted by traces of blood on a murder weapon.

As late as the 17th century, however, Western investigators were still prone to attributing unexplained deaths to supernatural causes. In 1691 the sudden death of Henry Sloughter, the colonial governor of New York, provoked public hysteria. It subsided after an autopsy performed by six physicians proved that blocked lungs, not spells or poison, were responsible. The case was a watershed in placing forensic pathology at the heart of the American judicial system.

THOMAS FUCHS

Growing confidence in scientific methods resulted in more systematic investigations, which increased the chances of a case being solved. In England in 1784, the conviction of John Toms for the murder of Edward Culshaw hinged on a paper scrap pulled from Culshaw’s bullet wound. The jagged edge was found to match up perfectly with a torn sheet of paper found in Toms’s pocket.

Still, the only way to determine whether a suspect was present at the scene of a crime was by visual identification. By the late 19th century, studies by Charles Darwin’s cousin, the anthropologist Sir Francis Galton, and others had established that every individual has unique fingerprints. Fingerprint evidence might have helped to identify Jack the Ripper in 1888, but official skepticism kept the police from pursuing it.

Four years later, in Argentina, fingerprints were used to solve a crime for the first time. Two police officers, Juan Vucetich and Eduardo Alvarez, ignored their superiors’ distrust of the method to prove that a woman had murdered her children so she could marry her lover.

The success of fingerprinting ushered in a golden age of forensic innovation, driven by ambition but guided by scientific principles. By the 1930s, dried blood stains could be analyzed for their blood type and bullets could be matched to the guns that fired them. Almost a century later, the first principle of forensic science still stands: Every contact leaves a trace.