BY LINDA KINSTLER

The Ascent of Woman

Enheduanna. Hatshepsut. Empress Wu. Murasaki Shikibu. These ancient women were the first feminist trailblazers, yet they’ve been largely expunged from the historical record.

Enheduanna, daughter of Sargon the Great of Sumer, became the world’s first recorded author in the third millennium BCE. Hatshepsut ruled the Kingdom of Egypt for 20 years, adopting the full regalia of a male king — beard included — before her successor had all signs of her reign erased. Empress Wu, also known as Wu Zetian, united the Chinese empire and reigned as sole monarch for fifteen years before her successors also tried to obliterate her achievements. Murasaki Shikibu wrote the world’s first novel, the Tale of Genji, between 1001-1010 AD. Her real name and personal details remain largely unknown.

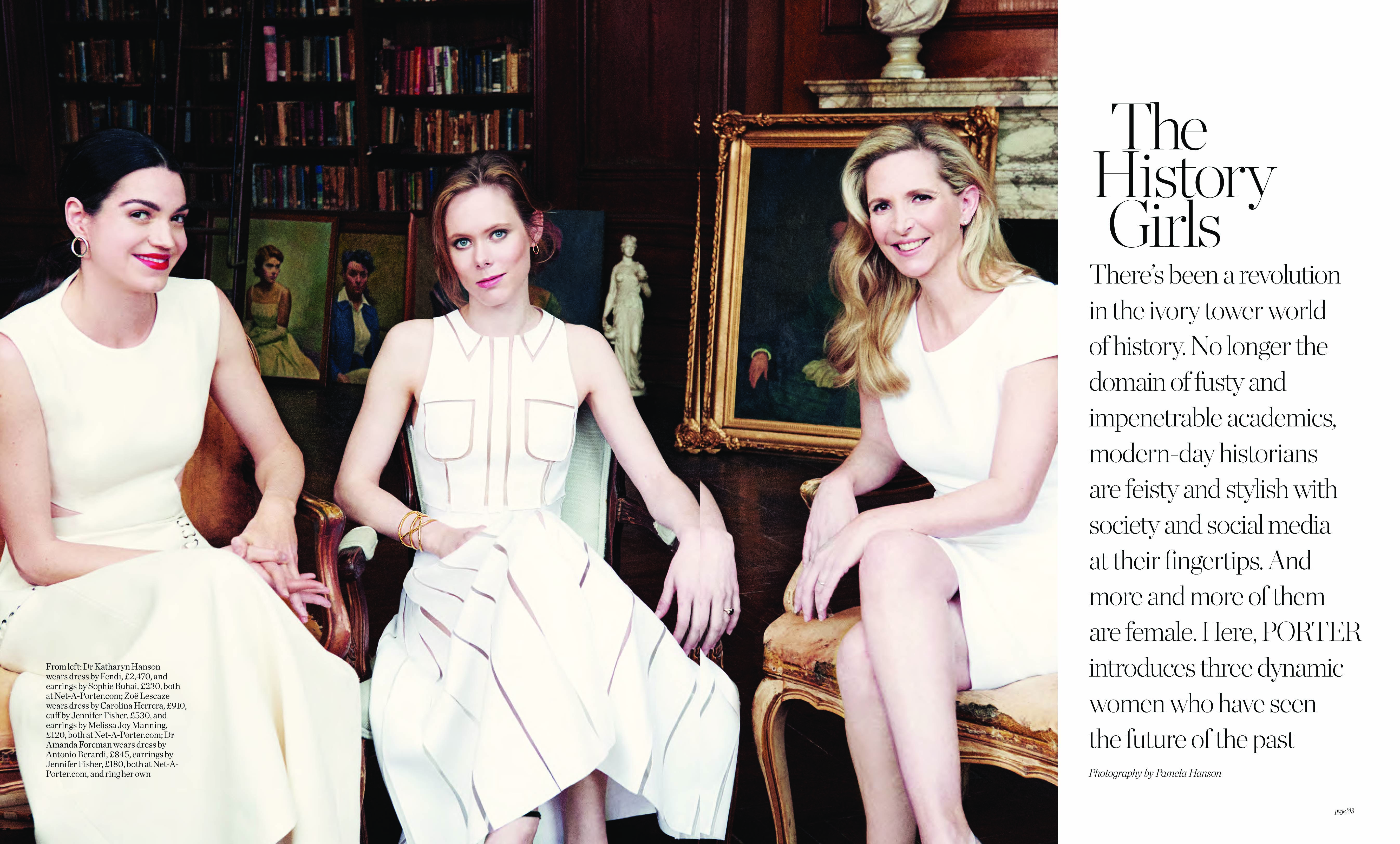

These influential women are just a few of the female iconoclasts featured in The Ascent of Woman, Dr. Amanda Foreman’s four-part BBC documentary that premiered to U.S. viewers on Netflix earlier this month. The series aims to “retell the story of civilization with women and men side by side for the first time,” as Foreman declares in the introduction. Reinscribing women into their rightful places in the human story, the documentary corrects the erasures of history’s male heirs. Continue reading…

The Tale of Genji

The Tale of Genji