As the Prince and Princess of Wales head stateside for their first US tour in eight years, Amanda Foreman assesses the British monarchy’s popularity across the Atlantic

November 26, 2022

Two royal events dominated the American headlines in 1981. The first was the great “curtsy scandal” in April, when the White House chief of protocol, Leonore Annenberg, was photographed curtsying to Prince Charles during his brief visit to the US. The idea of an American bending the knee to royalty — and English royalty no less — sent people into a frenzy of righteous indignation. There were editorials, letters, television debates, and seemingly endless outrage at the insult to American republican values. The State Department was forced to make a statement, and Annenberg never lived it down. Three months later, more than 14 million US households either stayed up all night or got up before dawn to watch Charles and Diana’s wedding.

As the French like to say, “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose”, the more things change, the more they stay the same. Four decades later, Americans are still viscerally tied and eternally conflicted about the royal family, only now they have been joined by two players from the other side who are pumping as much oxygen as possible to keep this psychodrama alive. The Duke and Duchess of Sussex’s move to California has made the volume louder, the talk trashier, and the stakes for the royal family never higher.

A two-hour chat with Oprah Winfrey turned a 70-year reign of selfless dedication and duty into a mere sideshow compared with the vital question of who said what to whom. Imagine what the Sussexes’ documentary series and Harry’s biography will do. With William and Kate, the new Prince and Princess of Wales, due to arrive in the US on Wednesday for a three-day trip — their first state visit since Queen Elizabeth’s death — there is going to be a royal smackdown of sorts that will allow a direct, peer-to-peer comparison between the working Windsors and the working-it Windsors.

If you believe the British press, the Sussexes are wearing out their welcome in the US. Their popularity is slipping down the scale, just like each episode of Meghan Markle’s Archetypes podcast on the Spotify rankings (down 76 places last week). But if that were actually true, the Sussexes would not be attending one of the most expensive charity galas in New York on December 6 to accept an award for their humanitarian work. The Robert F Kennedy Human Rights foundation, named after the younger brother of President John F Kennedy, is giving the couple the Ripple of Hope Award in recognition of their “heroic” fight against the royal family’s “structural racism”. Everyone knows that charity galas select their recipients with both ears and eyes focused on getting bums on seats. It’s the oldest game in town. Some charities even demand that they commit to buying a certain number of tables. There happen to be four other “name brand” recipients at the event, including the Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky, but they are being treated like the proverbial chopped liver compared with the excitement over having Harry and Meghan come to the East Coast.

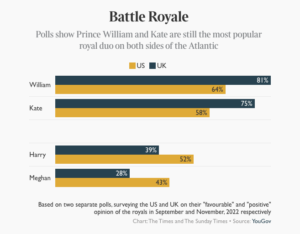

While the younger branches of two globally famous families make common cause in New York, that same week in Boston the John F Kennedy Library Foundation and the Royal Foundation will jointly award five £1 million Earthshot prizes to innovators in environmentalism. The Prince and Princess of Wales will be in attendance. Only 190 miles as the crow flies will separate the rival Windsor-Kennedys, but it could be a million or a trillion as far as their supporters are concerned. On paper, there is no question which event will be the more important or carries more gravitas. By every possible metric from the historic to the meaningful, the Waleses come out ahead. The Earthshot prize has the potential to save the planet. Its prizewinners are anonymous worker-bees not big shots who have made it to the top. But, to put it crudely, William and Kate are trading in yesterday’s currency. Leaving aside sheer sartorial glamour, where Kate is unmatched, the Waleses offer the world a fixed basket of virtues: duty, probity, discipline, decency, discretion, loyalty, and commitment. It is a worthy one, to be sure, and also totally — fatally — in step with the values of the over-40 crowd: Baby Boomers, Generation X, and some millennials. But the Duke and Duchess of Sussex are dealers in today’s currency: self-actualisation, self-healing, self-identity, self-care, self-expression, self-confidence, and self-love.

It is a duel representative of a cultural and generational divide in America. The Waleses and the Sussexes carry extraordinary weight — but it’s with their own constituencies rather than each other’s. The US broadsheets and magazines that cater to readers who were alive before the internet have been questioning for some time now whether the luxurious lifestyles of Harry and Meghan are out of kilter with their narrative of victimhood.

In August, New York Magazine published a 6,000-word interview with the duchess, rather cheekily entitled “Meghan of Montecito”, where she was given the opportunity to talk about herself without interruption. It was a risky decision to go beyond her natural fanbase on TV and social media. Unlike the infamous Oprah interview, the reporter kept a modicum of distance from her subject. One choice line read: “She has been media-trained and then royal media-trained and sometimes converses like she has a tiny Bachelor producer in her brain directing what she says.”

The medium was a poor fit for Meghan and the message that came across was less than flattering: she’s a piece of a work, he’s out of his depth. It made no difference, the podcast debuted at No 1 anyway.

The best way to understand the Sussexes’ relationship with ordinary Americans is to put it in the same context as Gwyneth Paltrow and her Goop lifestyle company. Goop was valued at $250 million in 2018, having started out as a newsletter in 2008. Experts routinely criticise the company for peddling expensive tat to credulous consumers who are chasing after something called “wellness”. Her supporters could not care less because they don’t need the products to be real, they just need them to be emotionally satisfying at the point of sale.

Harry and Meghan are selling something similar, call it “me-spiration”. It’s not a philosophy so much as an ego massage and it’s a pure money-maker. Netflix and Random House each have millions of dollars invested in its success. Random House is sitting pretty. Books dishing the dirt on the royal family always sell, no matter what. Netflix has more of a challenge on its hands. But an Oscar-winning screenwriter who spoke to me on the condition of anonymity revealed that the streaming company regards them in the same way they do the Obamas, who also have their own producing deal. The Sussexes must succeed because they are too expensive to fail. In any case, they have a star power that goes beyond the normal considerations of content or success because their brand is cross-collateralised with The Crown, still one of Netflix’s flagship series which regularly tops the streamers viewing figures in the US.

With two media juggernauts each working overtime to protect their assets, and a formula that milks two of the biggest obsessions in America today: royalty and identity, the Sussexes are assured their place in the social mediaverse. There will be no shortage of interviews, humanitarian awards, and self-generated documentaries in their future. The war between the Waleses and the Sussexes was over before it started.