Some holiday presents are so perfect, or so awful, that you remember them forever.

December 20, 2024

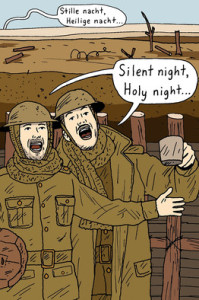

Christmas Eve. Things are not going according to plan.

Wind back: It’s T-minus 15 days to Christmas. I’m shopping for reindeer hats when my phone rings. That X-ray for my husband Reg’s sore rib? The problem isn’t his rib.

T-minus 12 days: He has cancer!

T-minus 9: Don’t worry. Our physician thinks they caught it early.

T-minus 7: Worry. The surgeon says it’s stage 4. “But there is always hope,” she tells us.

T-minus 2: Reg goes in for more tests.

T-minus 1: And another biopsy. Ouch.

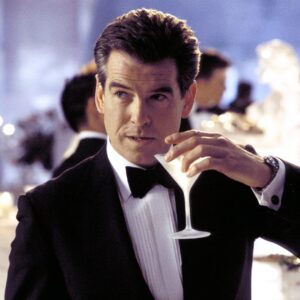

So here we are on a stormy Christmas Eve. I am driving to the country with unwrapped gifts in the trunk, five sleeping kids in the back and my semiconscious, possibly dying husband in the passenger seat.

My revised plan: Forget the turkey. Just wrap presents, stuff the stockings and sleep, so I’m not a wreck on Christmas morning.

Midnight: I’m ahead of the game.

2 a.m.: The wind has dislodged some roof tiles, and water is cascading through the children’s bedrooms to the dining room below. I find sleeping bags and herd the kids into the corridor. Yay! Christmas and camping, their two favorite activities. I don’t have enough buckets.

3 a.m.: Oh wait, I still need to do the stockings! I’d been thrilled to find ones that were the perfect Norman Rockwell red. Now, I hate them.

7:50 a.m. I think I dozed off. Only the reindeer hats to stuff.

8:00 a.m. Christmas Day! Reg is awake. His eyes widen when he sees me. “Why are you crying?” he asks.

“Everything. This. You.”

“Look at me,” he says. “I love you. I have everything I have ever wanted in you, our children, our life together. The only thing I no longer have is time.” Time. His words are the worst and best Christmas gifts rolled into one.

That was 15 years ago. It turned out there was hope—and more time, too.