Despite centuries of innovation, the humble 2,500-year-old ballot box is here to stay.

January 4, 2024

At least 40 national elections will take place around the world over the next year, with some two billion people going to the polls. Thanks to the 2,500-year-old invention of the ballot box, in most races these votes will actually count and be counted.

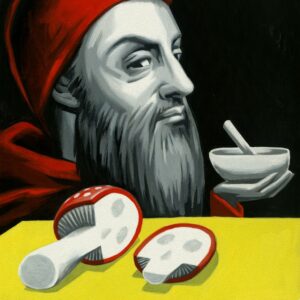

Ballot boxes were first used in Athens during the 5th century B.C., but in trials rather than elections. Legal cases were tried before a gathering of male citizens, known as the Assembly, and decided by vote. Jurors indicated their verdict by dropping either a marked or unmarked pebble into an urn, which protected them against violence by keeping their decision secret.

The first recorded case of ballot box stuffing also took place in 5th century Athens. To exile an unpopular Athenian via an “ostracism election,” Assembly voters simply had to scratch his name on an ostraka, a pottery shard, and whomever reached a certain threshold of votes was banished for 10 years. It is believed that Themistocles’s political enemies rigged his ostracism vote in 472 B.C. by distributing pre-etched shards throughout the Assembly.

In 139 B.C., the Romans passed a series of voter secrecy laws starting with the Lex Gabinia, which introduced the secret ballot for magistrate elections. A citizen would write his vote on a wax-covered wooden tablet and then deposit it in a wicker basket called a cista. The cistae were so effective at protecting voters from public scrutiny that many senators, including Cicero, regarded the ballot box as an attack on their authority and a dangerous concession to mob rule.

The fact that secret ballots allowed men to vote as they pleased was one reason why King Charles I of England ordered all “balloting boxes” to be taken out of circulation in 1637, where they remained until the 19th century.

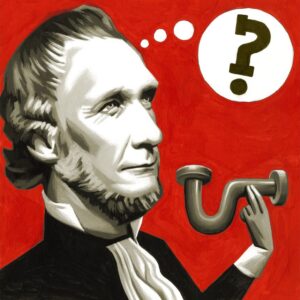

Even then, there was strong resistance to ballot boxes in Britain and America on the grounds that they were unmanly: A citizen ought to display his vote, not hide it. In any case, there was nothing special about a 19th-century ballot box except its convenience for stealing or stuffing. One notorious election scam in San Francisco in the 1850s involved a ballot box with a false bottom.

Public outrage over rigged elections in the U.S. led some states to adopt Samuel Jollie’s tamper-proof glass ballot box, which New York first used in 1857. But a transparent design couldn’t prevent these boxes from mysteriously disappearing, nor would it have saved Edgar Allan Poe, who is thought to have died in Baltimore from being “cooped,” a practice where kidnap victims were drugged into docility and made to vote multiple times.

To better guarantee the integrity of elections, New York introduced in 1892 a new machine by Jacob Myers that allowed voters to privately choose candidates by pulling a lever, which dispensed with ballots and ballot boxes. Other inventors quickly improved on the design and by 1900 Jollie’s glass ballot box had become obsolete. By World War II almost every city had switched over to mechanical voting systems, which tallied votes automatically.

The simple ballot box seemed destined to disappear until controversies over machine irregularities in the 2000 presidential election resulted in the Help America Vote Act, which requires all votes to have a paper record. The ballot box still isn’t the perfect shield against fraud. But then, neither is anything else.